A guide projected to vine sales: Experiences from Ghana and Malawi through community-base research demo-trials

Erna Abidin (Reputed Agriculture for Development Stichting/Foundation)

Introduction

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) crop is widely grown in tropical, sub-tropical and temperate areas between 40° N and 32° [1][2][3]. Well-drained, light and medium textured soils with a pH range of 4.5-7.0 are most suitable for the crop[4][5][6]. It is not necessary to apply lime unless the soil has a high aluminum concentration since sweetpotato is sensitive to Aluminum toxicity and will die about 6 weeks after planting if lime is not applied in soils where this is a problem[3]. Best growth is obtained with temperatures above 24°C, abundant sunshine and warm nights. Annual rainfall of 750-1,000 mm is considered most suitable, with a minimum of 500 mm in the growing season. The crop is sensitive to drought at the storage root initiation stage 3 to 5 weeks after planting, and is not tolerant to water-logging, as it may cause rots and reduce growth of storage roots if aeration is poor[4]. However, the crop can continue growing with little soil moisture once the root system has established well, and the canopy has spread to cover the soil. The deep rooting system penetrates the soil up to 0.9 m and allows the crop to continue growing robustly. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria of the Azospirillum genus are found in association with roots of sweetpotato[4]. This can improve the soil condition and fertility in the drought-prone areas and sweetpotato can be used as cover crop for agricultural industrial crops with a good field management plan. Hence, we can still bring the sweetpotato crop to continue serving a nutritional function in food and nutrition security in sustainable livelihood systems. Industrial crops may be chosen for this, for instance palm oil, cacao, rubber, black and white pepper plantation, etc.

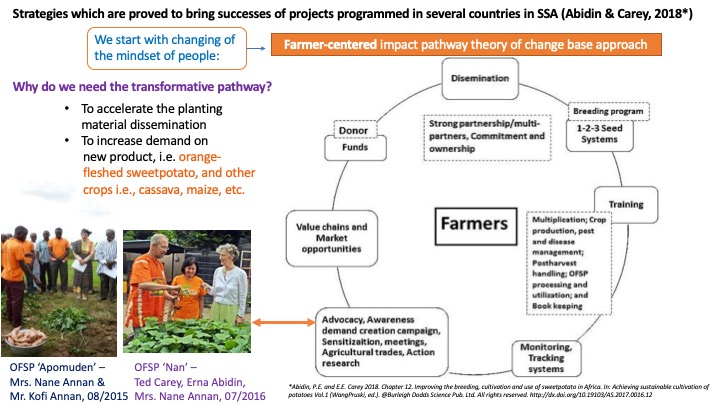

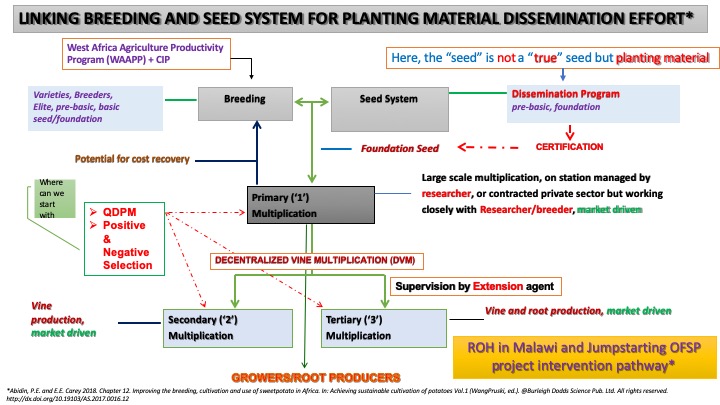

Sweetpotato breeding in West Africa linkage in sweetpotato dissemination program

The national agricultural research and extension services (NARES) together with the International Potato Center (CIP) breeding program for sweetpotato improvement in West Africa have focused on producing a number of released sweetpotato varieties in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria. There has an effort to produce pathogen-tested planting material of these varieties to be readily available to sweetpotato farmers through commercial vine multipliers. A big effort by CIP started in 2010 and included several proof of concept projects working on value chains and market structure along with the promotion of the orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) and other types of sweetpotato varieties for health and wealth. The Crop Research Institute (CRI) in Kumasi already released the OFSP variety Apomuden in 2005, and had released several other varieties previously, but the remarkable value of sweetpotato, and particularly OFSP as a nutritious food was not well recognized. Currently there are 3 released OFSP varieties in Ghana, i.e., Apomuden, Nan (deep orange) and Bohye (light orange) as well as a purple fleshed sweetpotato (PFSP) variety, Diedi (original name: TU-Purple). Recently CSIR-SARI released its first varieties, white fleshed sweetpotato (WFSP) Obari which is already commercial variety in northern Ghana (Bawku), Nan and Diedi. Through the project, Jumpstarting OFSP in West Africa, protocols for quality declared planting material (QDPM) were developed and promoted to ensure best quality when selling good quality sweetpotato planting material to buyers and end-users. The CIP-led project, Jumpstarting OFSP in West Africa demonstrated that sweetpotato planting materials can be readily sold to market-oriented farmers who have access to reliable markets. The fresh roots can be sold in open or structured markets[1] as well as to agro-industries once a consistent supply is available. Potential to effectively tap into export markets for fresh roots is affected by the same challenges of consistent supply. Contract farming can be a solution for keeping the consistency of supply chains. Establishing the sweetpotato value chains can be strengthened through emphasis on value addition through fully and/or half-processed products, such as puree, gari (composited with cassava), and flour. CIP has introduced various recipes made from sweetpotato for supporting its interventions[2]. Sweetpotato puree presents a very economically interesting option for processing of sweetpotato, as it can be used as an ingredient in a range of baked and prepared products including bread, baby food, juices, soups, etc. An attractive point of puree is the retention of nutritional value. OFSP bread, pastry products and gari are accepted by consumers, but consistency of sweetpotato supply to processors remains a challenge. There is a need to take a value chain approach with private sector partners to ensure scaling and massive adoption.

Promoting the utilisation and processing of sweetpotato to significantly increase demand through sweetpotato value chains

Various dishes incorporating sweetpotato into important local foods were developed aimed at helping accelerate the demand created in the target societies[6]. These recipes were, then introduced during awareness creation interventions. It has shown a significant result in increased demand and adoption according to a number of literatures some of being listed in this blog. Meals from OFSP are included on the menu of the school feeding programme in Osun State (Nigeria)[1] and were also tested in the school feeding intervention in Kumbungu District of North Region of Ghana. Positive responses were obtained from stakeholders including local governments, school children and their families, caterers, and root producers. We fully expect that private sector engagement can play an important role in upscaling sweetpotato for sustainability in countries where the sweetpotato crop has been introduced. And provision of quality planting material in the quantities needed at the time of planting is a key element for a success.

This document presents a protocol for production of quality declared planting material (QDPM) for sale. Sweetpotato vine multipliers and root producers can make use of it to guide them to become reliable suppliers within the sweetpotato value chains in their countries.

Simple Calculation of sweetpotato vine multiplication for small-scale farmers

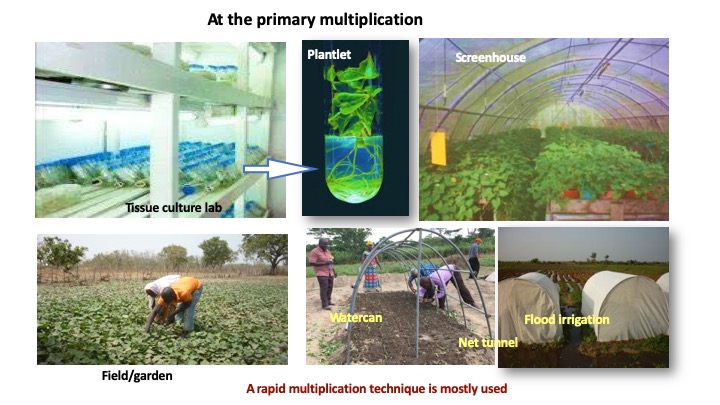

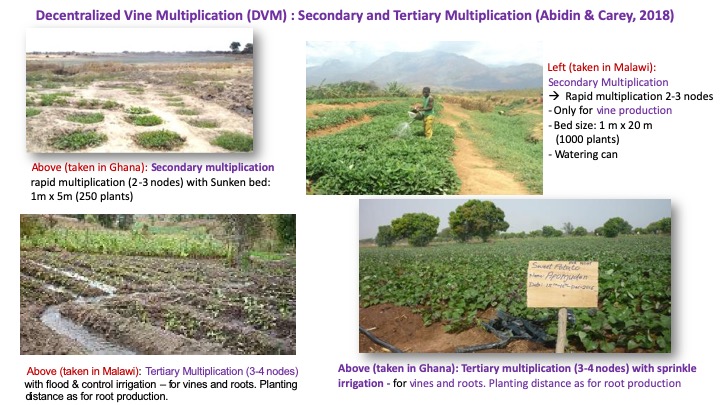

When farmers start growing the sweetpotato crop, they usually do not have enough planting materials. CIP-led projects in Malawi and Ghana have introduced simple calculation of vine cuttings and use of rapid multiplication method. The healthy vine cuttings should be bought from a reliable source, such as from the registered vine producers or trained Decentralised Vine Multipliers (DVM).

Bed preparation for vine multiplication

A fertile, well-drained soil is preferred for sweetpotato vine multiplication and production. For rapid multiplication of vines in beds, a high density planting is done, with beds raised 15 – 20cm. Nitrogen will stimulate rapid vine growth, and an organic fertiliser such a poultry manure will provide a slow-release source of nutrients, in addition to improving soil organic matter. Rate of application can be determined following CABI guidelines[8], with manure incorporated into the bed one to two weeks before planting. Inorganic fertiliser sources can complement manure or composts applications, particularly following harvest of vines when regrowth of vines will be stimulated by application of N-fertiliser. Photos were taken at El-Green Agro-business Ltd., Agona Ashanti, Ghana. We consciously used GAPs including smart-agriculture approach and minimum tillage technique for soil conservation; and chicken manure to improve the soil fertility.

Standard sized beds are used to easily calculate anticipated numbers of vines to be produced, either for vines or root production. Furthermore, the one-meter width of beds can help to protect the sweetpotato plants on the bed from unintentional damage by careless field labor during maintenance. Hence, nobody is walking over the plants because the plants can be easily reached from either side of the bed.

A. Vine cuttings for vine production

- Cultivate the initial 250 vine cuttings by following technique:

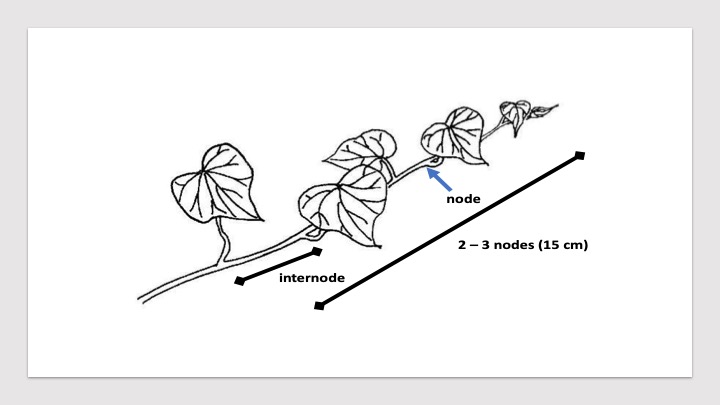

- We use 3 nodes (~15 cm) of vine cutting as a planting material

- Planting distance: 20 x 10 cm

- Use standard bed for further planning on the next planting

(1) If the standard bed of 1m x 5 m, 250 vine cuttings are needed

(2) If the standard bed of 1m x 10 m, 500 vine cuttings are needed; i.e. 2*250 vine cuttings

(3) If the standard bed of 1m x 20 m, 1,000 vine cuttings are needed; i.e. 4 * 250 vine cuttings

(4) 1 ha of land, 500,000 vine cuttings are needed, then, prepare 500 plots of each 1 m x 20 m

Using GAPs, your sweetpotato plants are healthy and happy as seen them in the following picture.

- Harvest the plants from the first bed of 1m x 5m for the next vine production

First Harvest: 1 to 1.5 months after planting (MAP), we can harvest the 250 plants with an average length of 90 cm. It depends on sweetpotato varieties.

- Harvest 75 cm out of 90 cm vines for immediate multiplication, leaving 15cm stem at the base for re-growth.

- The 75 cm stem can produce 5 vine cuttings 2-3 nodes long.

- A total of 1,250 vine cuttings are obtained from 250 plants.

- Prepare another 5 beds with the same size plot of 1 x 5 m

- Plant 250 cuttings of 2-3 nodes (as described under point 1 above) on each 1m x 5m bed.

- The initial plot can be maintained while the new beds grow. Fertilisation is recommended following harvest of vines in order to stimulate re-growth.

The following pictures have shown 3 sweetpotato varieties at 1.5 MAP taken at El-Green Agro-Business Ltd., Agona-Ashanti Ghana in 2019.

- Harvesting 6 beds at the same time, a month later

This is the second harvest of the vines in the multiplication plan and it should be done when vines are ready, normally one month after planting or initial harvesting of the first bed.

- From the initial plot of 1m x 5m, the remaining plant having 2-3 nodes will produce 2 stems of each 90 cm long on average. The vine cuttings harvested will be 500 vines (2 x 250 plants).

- From the newly-planted beds we can harvest 1,250 plants each 90 cm long in average. This number comes from the 5 beds, each having 250 plants.

- Thus, we can obtain a total of 1,750 vines 90 cm long at 2 MAP, which will result in 7000 vine cuttings for root production.

B. Vines for root production

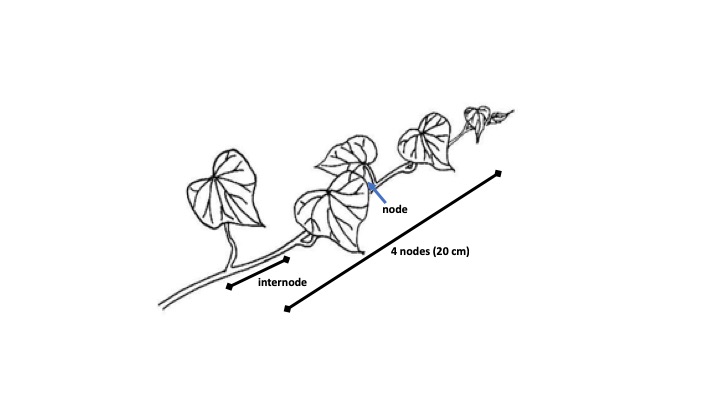

- We use 3-4 nodes (~20cm long) of of vine cuttings as a planting material.

- Each 90 cm long vine harvested from the nursery beds can produce 4 vine cuttings each with ~4 nodes (~20 cm), leaving a 10 to 15 cm base to re-sprout for further vines for root production.

- A total of 7000 vine cuttings generated from the nursery. The calculation should be 4 vine cuttings x 1,750 plants harvested from 6 plots.

- In 1 ha, we need 33,000 vine cuttings. If we have 7,000 vines, then we can cover the land of 0.21 ha with sweetpotato crop.

- In another month we can expect 12,000 cuttings 20 cm long, enough to plant an additional 0.36 ha.

Recommendation

Sweetpotato vine multipliers need to pay attention to the timing of preparing the nursery beds, at least 2 to 3 months before selling sweetpotato vines for root production.

Acknowledgement: The author acknowledges Dr. Edward E Carey who went through it and has given his valuable contributions.

DECLARATION OF NO CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interests from the author when writing this guidance. However, as part of the objectives from the Reputed Agriculture 4 Development Stichting (The Netherlands) and/or Foundation (Ghana), as a non-profit NGO, our NGO needs to accomplish improved skills and knowledge on sweetpotato multiplication for farmers/growers. In this case, our target is the small-scale business farmers or people who are taking gardening as a hobby. I do have the skills and knowledge based on many years of experiences as a sweetpotato seed system scientist for CGIAR-CIP. Mostly, the proof-of-concepts of donor-funded projects which I have led, have shown great impacts on adoption, increase of food security, improved nutrition and wealth in the countries where the projects were taken place.

I wrote this guide as part of an information, communication and education (IEC) materials from which I had my opportunities of developing my experiences in education in the last ~35 years in Indonesia, at Wageningen University (extra curriculum on “Didactic Skills” during my MSc of which allowed me to teach at the high education systems), Uganda, Malawi, Ghana, Nigeria and Burkina Faso for implementing them on the ground. I would like to sincerely acknowledge the Ministry of Agriculture of Indonesia, Wageningen University, Netherland Ministry of Foreign Affairs through PSO, Ministries of Agriculture and Education of Uganda, CIP and its funded projects by Irish Aid, USAID-OFDA, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), and the Governments of Malawi, Ghana, Burkina Faso and Nigeria for allowing me to implement my skills and knowledge in Agricultural Education in general in their countries.

References

[1] Purseglove, J.W. 1991. Tropical crops. Dicotyledons. Longman Scientic and Technical, John Wiley and Sons, Inc. NY. USA.

[2] Woolfe, J.A. 1992. Sweetpotato: an uptapped food source. Cambridge Univ. Press and the International Potato (CIP). Cambridge, UK.

[3] Ahn, P.M. 1993. Tropical soils and fertilizer use. Intermediate Trop. Agric. Series. Longman Sci., and Tech., Ltd. UK.

[4] Hill, W.A., P. Bacon-Hill, S.M. Crossman and C. Stevens 1983. Characterization of N2-fixing bacteria associated with sweetpotato roots. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 29(8): 860-62.

[5] Abidin P.E., S. Adekambi, J. Nchor, I. Koara and E.E. Carey 2017. An orphan crop the Orange-Fleshed Sweetpotato, in West Africa: Can we reposition it?. Research & Reviews: Journal of Botanical Sciences Vol 6 (4): 37-40. E-ISSN:2320-0189/P-ISSN: 2347-2308.

[6] Abidin et al. 2015. Training of trainers’ module for orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) utilization and processing. CIP. 32pp. Available at https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/64872

[7] Lagerkvist C.J., J.J. Okello, S. Adekambi, N. Kwikiriza, P.E. Abidin, and E.E. Carey 2018. Goal-setting and volitional behavioural change: Results from a school meals intervention with vitamin-A biofertified sweetpotato in Nigeria. Appetite 129: 113-124.

[8] Abidin, P.E., K. Sones and E.E. Carey 2017. Africa Soil Health Consortium: Sweetpotato cropping guide. CABI Pub., 61pp, available at http://africasoilhealth.cabi.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ASHC-English-sweet-potato-A5-colour-lowres.pdf.

We are pleased to invite you to see our blog about orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) and cassava gari, next.

Please share this info with others through twitter

Tweet